…a management methodology that helps ensure that the company focuses efforts on the same important issues throughout the organization

—John Doerr, Measure What Matters

Applying OKRs in the Scaled Agile Framework

[scd_58689 title=”extended-guidance”]Introduction

Objectives and Key Results, commonly referred to as OKRs, is a goal-setting framework focused on providing objective evidence of progress (Key Results) toward achieving a set of business outcomes (Objectives).

When used within SAFe, OKRs can help to support the Core Values of transparency and alignment between the Enterprise and Portfolio strategy, and the work of the Agile Release Trains and Agile Teams to deliver on this strategy. Additionally, OKRs can be applied to measure organizational improvement activities, including the desired outcomes for the SAFe transformation itself.

While this article describes opportunities to apply OKRs within SAFe, their usage is optional, apart from the strong recommendation to use them to describe portfolio Strategic Themes. If a decision is taken to apply OKRs, these must be applied within an environment conducive to their success. The benefits of OKRs will only be realized where planning and delivery are incremental, ensuring the ability to respond to the continuous feedback that OKRs provide. Enterprises that still employ traditional development methods, with an upfront commitment to large batches of work, will often struggle to reap the benefits of OKRs. We will conclude this article with a special caveat where OKRs do not work as well as you might anticipate.

Details

Since their invention by Andy Grove at Intel and the subsequent, well-publicized adoption at Google in 1999, many leading technology companies have embraced Objectives and Key Results (OKRs). They are used to create aspirational goals that drive higher organizational performance and employee engagement [1].

The simplicity of OKRs goes a long way to explaining their popularity. The ‘Objective’ defines the business outcome that you are striving to achieve. The ‘Key Results’ are the measurable success criteria used to track progress toward the objective. For each objective, there is typically between two to five key results [2]. An example OKR, used to define a SAFe strategic theme, is shown below in Figure 1.

Writing Well-formed OKRs

Well-written OKRs can be effective in aligning individuals and teams to measurable outcomes, but poorly written OKRs may have the opposite effect. Common anti-patterns include describing business as usual activities in place of aspirational goals, focusing on outputs rather than outcomes, and defining key results that describe a list of tasks or deliverables.

In contrast, well-written Objectives have the following qualities:

Inspirational: Each objective should describe an important and worthwhile goal. The objectives should be ambitious and move people out of their comfort zone to strive to achieve more. In short, they should inspire people to act.

Clear and Memorable: Objectives should be written succinctly in clear, memorable terms. Furthermore, there should not be too many objectives, 3-5 is typical. The objective itself should be qualitative and not include numbers. These will come later in the key results.

Committed or Aspirational: Each objective should be marked as either committed or aspirational. Committed objectives describe things that must be done, such as meeting changes in legislation, whereas aspirational objectives are things that we hope we can achieve. We strive to achieve 100% of our committed objectives while a 60-70% achievement is more realistic for aspirational objectives.

Doing Work or Improving Work: An additional distinction that may be useful is recognizing which objectives are related to developing or incrementing the Solution and which are focused on improving processes. The former is measured with business-orientated key results, while the latter will likely use a combination of SAFe flow metrics. (An example of an improvement OKR is provided in use case 3 below).

Each objective is typically accompanied by 2 – 5 key results. Well-written key results have the following qualities:

Value-based: Key results should describe desired outcomes rather than the activities that drive these outcomes. Getting this right can be challenging. To move from activities to outcomes, the following questions can be helpful:

- What is the desired impact of this activity?

- How will I know this activity had an impact?

- What is the measurable result I hope to achieve in doing this activity?

Measurable: Each key result should be measurable and accompanied by a target number. Ideally, across all the key results, a mixture of leading and lagging indicators should allow you to measure progress at different times.

Gradable: The key results should also be gradable. In other words, we should be able to measure how much of that outcome has been achieved. This contrasts with key results that have a simple yes or no response. Typical formats for expressing gradable key results include:

- Should increase from X to Y

- Should decrease from Y to X

- Should stay above X

- Should stay below Y

The example below illustrates how applying this guidance to create well-written OKRs helps to move the conversation from output-focused OKRs to outcome-focused OKRs:

Applying OKRs in SAFe

As mentioned previously, the application of OKRs in SAFe is optional. The following three use cases describe potential applications, although this list may not be exhaustive. Consider the benefits they might bring to your organization for each of these. Be mindful that too many use cases implemented at once may create overheads that outweigh the benefits.

The application of OKRs within SAFe falls into three main use cases, illustrated in Figure 3 below:

- Enhancing strategic alignment across a SAFe portfolio

- Defining business outcomes for epics and lean business cases

- Setting improvement goals for the SAFe transformation

Each of these is described in more details below.

1. Enhancing Strategic Alignment across a SAFe Portfolio

A SAFe portfolio governs a set of value streams and the solutions they develop and deliver. Alignment must be maintained between the portfolio and the enterprise strategy, and across the portfolio itself. Strategic themes provide the requisite transparency to ensure this alignment across the value streams and ARTs within the portfolio. SAFe recommends using OKRs for defining strategic themes, as shown in Figure 1 above, as it provides an effective means to define, organize and communicate these critical differentiating business objectives.

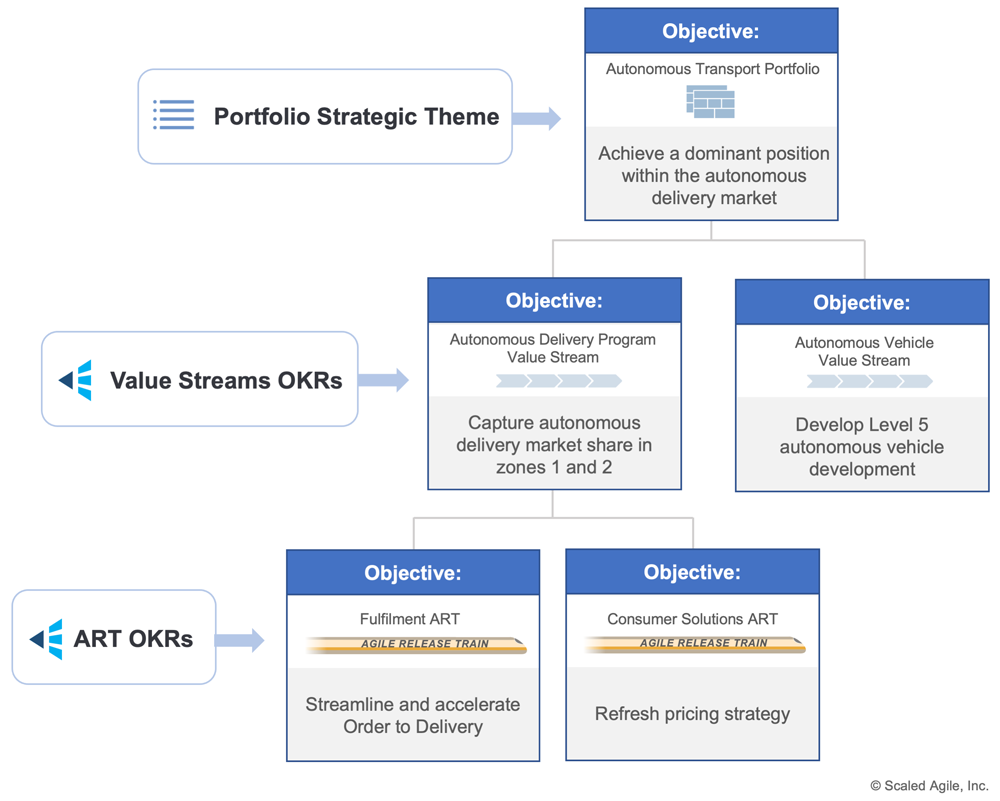

Defining Value Stream and ART OKRs

Strategic themes often don’t impact all value streams in a portfolio equally; the work to execute against a particular strategic theme will be different for each value stream. Therefore, it can be helpful to create specific OKRs for each value stream, that align with the portfolio strategic themes. And further, for large value streams that contain multiple ARTs this process can be repeated to create a set of OKRs that define the goals for each specific ART. Figure 4 below shows how these different levels of OKRs work together to provide alignment and transparency at multiple levels.

This approach also allows those at each level of the organization to see the direct impact of their work against the key results of the OKRs they are aligning to. This contrasts with the situation where goals are typically defined only at the highest level within the organization. And in the same manner that the portfolio strategic themes influence key decision making within each portfolio, value stream and ART OKRs become a critical tool for Solution and Product Managers, and Solution and System Architects when developing their roadmaps and exploring and prioritizing new opportunities.

OKRs inform Value Stream and Solution KPIs

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) provide a set of measures that help to evaluate how a value stream or ART is performing against its forecasted business outcomes. OKRs play a key role in informing and defining these KPIs.

NOTE: The difference between OKRs and KPIs: Whereas OKRs define the specific objectives that we are working towards in order to achieve future success, KPIs represent ongoing ‘health’ metrics that can be used to measure overall business performance.

Value stream KPIs will be influenced directly by the portfolio strategic themes, which set clear expectations around the key results that must be delivered or supported. (This process is discussed further in the Value Stream KPIs article.) However, as explained above, specific OKRs can also be defined for value streams and ARTs. In this situation the associated key results can be used to define KPIs for a particular solution that the ART is developing.

The Fulfilment ART from Figure 4, is developing a ‘delivery notifications and communication platform’ to meet the goals outlined in its ART-specific OKRs. By analyzing the key results of those OKRs the following 5 solution KPIs emerge.

- Cost per notification

- Time to communication

- Missed deliveries

- Error rates in notifications

- Customer engagement

These solution KPIs not only help to measure the overall business outcomes from the current work, but will continue to persist and evolve, separate to additional epics that get defined. In this manner they provide a higher-level view of whether our solutions are achieving their expected business outcomes.

Measuring Progress against OKRs

OKRs they provide a means to continually measure progress, allowing the organization to take the necessary corrective actions or amplify successes. Each key result is measurable and should be gradable on an implicit scale, typically a percentage. However, because changes in strategy take time to apply, a quarterly cadence for measuring and reporting against key results is recommended. The Strategic Portfolio Review is the ideal event to reflect on the progress being made. Figure 5 shows a set of key results measured quarterly.

The benefits of having multiple key results attached to each objective should be clear from this example. No single key result can provide the complete picture in isolation. Some are improving based on the work that has been done, while others are going in the wrong direction. These multiple perspectives provide the inputs required to reflect on necessary changes to the plan.

Of course, getting feedback in this manner requires two critical things. Firstly, the ability to deliver value often, and thereby incrementally measure the progress made. This requires investment in the Continuous Delivery Pipeline and the ability to continuously deploy and release value on demand. Secondly, the ability to measure must be built into the solution. For each key result defined, the question should be asked, ‘how are we going to measure this?’ In many instances, this will require solution telemetry, which must be part of the solution development activities.

2. Defining Business Outcomes for Epics and Lean Business Cases

Once the OKRs have been defined, these play an essential role in helping to uncover potential Epics for entry into the Portfolio Kanban system, as shown in Figure 6. The question that arises is, ‘What work do we need to do to affect a positive change in the key results that we have defined?’ This ensures alignment amongst those contributing ideas and an objective means of either approving or removing ideas from the funnel. Furthermore, for the epics that proceed to implementation, the connection to the strategy is clear for all those working on them.

Epic and Lean Business Case Definition

OKRs can also play an essential role in epic definition, specifically when clarifying the desired business outcomes. The business outcomes are those measurable benefits that the business can anticipate if the epic hypothesis is correct. Applying OKRs to describe the business outcomes ensures that they are outcome-focused and measurable. An example is shown in Figure 7 below. OKRs used in this manner as part of an Epic Hypothesis Statement or Lean Business Case may also inform portfolio prioritization conversations.

The next step in the lifecycle of an epic is to move it through the SAFe Lean Startup Cycle. Here the goal is to define a Minimal Viable Product (MVP) used to either prove or disprove the epic hypothesis as quickly as possible. Therefore, the outcomes that this MVP is testing need to be clearly defined and measurable for us to make an appropriate pivot or persevere decision. Once again, OKRs can provide this clarity. The objective defines the expected outcome of an MVP, and the key results represent the conditions that would prove the objective to be true, as shown in Figure 8.

3. Setting Improvement Goals for the SAFe Transformation

OKRs can also be used to good effect to set outcomes for the SAFe transformation itself. Multiple opportunities for applying OKRs exist, often falling into a hierarchy of outcomes as shown in the figure below:

In this scenario, the OKRs will predominantly fall into the ‘improving work’ category, typically focusing on improving quality, time to market, and predictability. An example of an improvement objective and key results is shown below.

Applying OKRs to the SAFe transformation also forces early discussion around expected benefits. This generates the alignment and transparency previously described, and it also creates commitment to the journey that is about to begin.

A Special Caveat: OKRs and PI Objectives

Special mention is deserving of the application of OKRs to writing PI Objectives. The typical format for describing PI Objectives is to make them S.M.A.R.T. On the surface, it would seem a simple endeavor to change this to the OKR format. However, there are reasons we caution against this.

We must be mindful of the time it would take to write, review, and eventually assess, the team PI objectives in the OKRs format. S.M.A.R.T. objectives can typically be expressed in a single sentence or phrase. OKRs are much deeper and take more time. Teams have limited time during PI Planning, and drafting objectives, each with 3-5 key results, leaves less time for the actual planning activities. Furthermore, key results often represent lagging indicators and may not be achievable within the PI timebox.

Summary

The benefits of OKRs in creating alignment and supporting transparency are well documented, and within SAFe, they play a crucial role in defining strategic themes. Over time SAFe enterprises have also seen benefits in applying them in the other scenarios described above. When deciding whether to implement them in these additional ways, the expected benefits need to be carefully considered against any additional overheads in creating and maintaining them.

Finally, it should be recognized that OKRs can also fall victim to the same problems as the more traditional ways of defining outcomes. An organization that struggles to move the conversation to focus on business outcomes will only realize the benefits of OKRs if they ensure they are well-constructed and can measure progress against them on an ongoing basis. However, when done correctly, they provide an effective tool to help you drive better outcomes for your business and customers.

Learn More

[1] Doer, John. Measure What Matters. [2] Castro, Filipe. The Beginner’s Guide to OKRs.

Last update: 2 June 2022